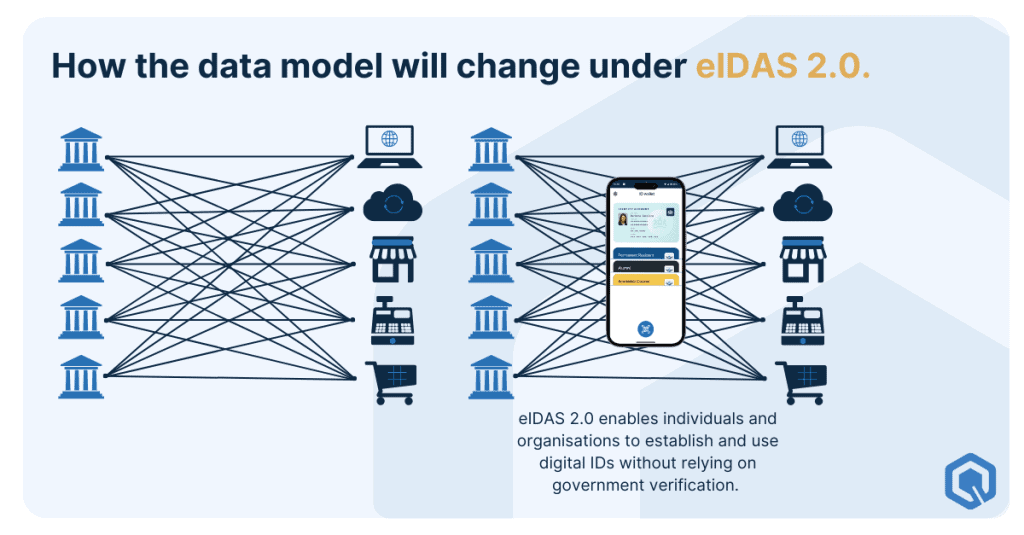

Digital wallets are designed to make it easier and safer to share verified information – for example, proving your age, identity, or qualifications online. They connect the people or organizations that issue data, the users who hold it, and the services that need to check it. But running that system isn’t free. Every time a digital proof is created, stored, or checked, it relies on secure technology and trusted services – and someone has to cover those costs.

That’s what Boris Goranov, CEO of Ubiqu, discussed in his presentation “Layering credential payments on top of the existing eIDAS 2.0 infrastructure” at Obserwatorium.biz. He outlined four payment models that could define how Europe’s digital identity ecosystem will sustain itself: the issuer pays, the user pays, the relying party pays, or the ecosystem pays.

How trust used to work and why that’s changing

In the old days, trust was visible. It meant stamped and signed papers that you picked up, carried to another office, and handed over to prove something about yourself. You trusted the paper because you could see where it came from, and the institution trusted it because it recognized the seal.

Now that processes are moving online, that visibility is disappearing. Instead of trusting the paper, we start trusting the connection. Encryption, certificates, and secure servers take over the role of the ink stamp. It makes processes faster, but it also hides the cost of trust inside technology that most people never see. With digital wallets, that cost and responsibility become visible again, and the question arises: who will pay to keep the system running?

Four possible ways to pay for digital trust

There are four main models for funding digital wallets and the infrastructure around them. Each reflects who benefits most from the transaction and who is in the best position to fund it.

- The issuer pays. The issuer is the organization that provides the verified data, such as a government issuing an ID, a university issuing a diploma, or a bank issuing a financial credential. In this model, that organization funds the system as part of its role or strategy. It treats identity verification as a public duty or as something that strengthens its position in the market.

- The user pays. The user is the individual who holds and presents the credential. This person covers the cost directly, similar to how people already pay for passports, birth certificates, or driving licences. The logic is simple: if you need a verified proof of something, you pay a small amount to get it.

- The relying party pays. The relying party is the organization that needs to verify someone’s data, such as an employer checking a qualification, a landlord confirming income, or a bank verifying identity. Because these organizations benefit most from reliable and instant verification, they cover the cost of using the data.

- The ecosystem pays. The ecosystem is the collective network that makes digital trust possible, including governments, service providers, technology vendors, and sometimes EU programs. In this model, these parties share costs to maintain the underlying infrastructure as a public service. It ensures that the system remains neutral and accessible for everyone who depends on it.

The issuer pays when trust is a strategic investment

In this model, the organization that issues credentials also covers the cost of verification and wallet integration. This approach makes sense for entities that see verified data as part of their public duty or strategic interest. A government might fund identity verification because it benefits the wider economy and reduces fraud. A private issuer, such as a large platform or bank, might do the same if offering credentials strengthens their ecosystem and attracts more users.

The trade-off is that costs remain internal while benefits are external. Governments can absorb this through public budgets, but private issuers risk creating a free service for others to profit from. Over time, this model works best where trust has a clear public benefit or a strong indirect return, not when credential issuance is just another operational process.

The user pays when speed and convenience outweigh cost

Here, the person who needs the credential covers the fee directly. This already happens in the physical world: people pay for passports, birth certificates, and driving licences. The same logic could apply digitally, with small per-issuance fees or micro-payments for single-use credentials. It is transparent, easy to manage, and keeps the model simple.

The challenge is accessibility. Not everyone will pay for every credential they might need, especially for low-income citizens or minor transactions. The system could become inequitable or drive people back to slower manual processes. User-pays models only work when the value to the individual is immediate and clear, for example when paying a few euros can reduce weeks of administrative delay.

The relying party pays when data is a business enabler

Relying parties are the organizations that request verified data, such as banks, housing associations, employers, or service providers. They depend on accurate, trusted credentials to operate efficiently. In this model, the relying party pays because it benefits most directly from faster onboarding, reduced fraud, and smoother transactions.

An example is the social housing process in Rotterdam, where applicants wait weeks for a paper income statement from the tax office. With a digital wallet, that verification could take minutes. The housing provider gains a faster process and happier applicants, which justifies a transaction fee or service payment. The main challenge is coordination. Relying-party models require technical or contractual mechanisms to ensure payment per verification and balanced incentives so that issuers continue to participate.

The ecosystem pays when trust becomes shared infrastructure

Some trust layers are so fundamental that no single party can or should bear the full cost. The ecosystem model spreads funding among governments, service providers, and sometimes EU programs to maintain the infrastructure collectively. It mirrors how core internet services such as DNS or PKI are funded: everyone depends on them, so everyone contributes.

The advantage is long-term sustainability and fairness. The drawback is complexity. Collective funding demands coordination across sectors, regions, and political boundaries, which can slow implementation. This model works best for foundational layers such as certification authorities, wallet frameworks, and common APIs, where neutrality and public benefit are more important than commercial competition.

Trust always comes with a bill

Each model reflects a different balance between value and responsibility. The issuer model aligns with strategic or public-interest goals. The user model rewards convenience. The relying-party model links cost to direct benefit. The ecosystem model sustains shared infrastructure. None of them stand alone, but the success of digital wallets in Europe will depend on how these models are combined in practice.

Digital wallets are, in the end, a data pipe. But even pipes need maintenance. The organizations and individuals who gain most from trusted data exchange will have to decide how to share the cost, because trust always comes with a bill.